Chapter 6

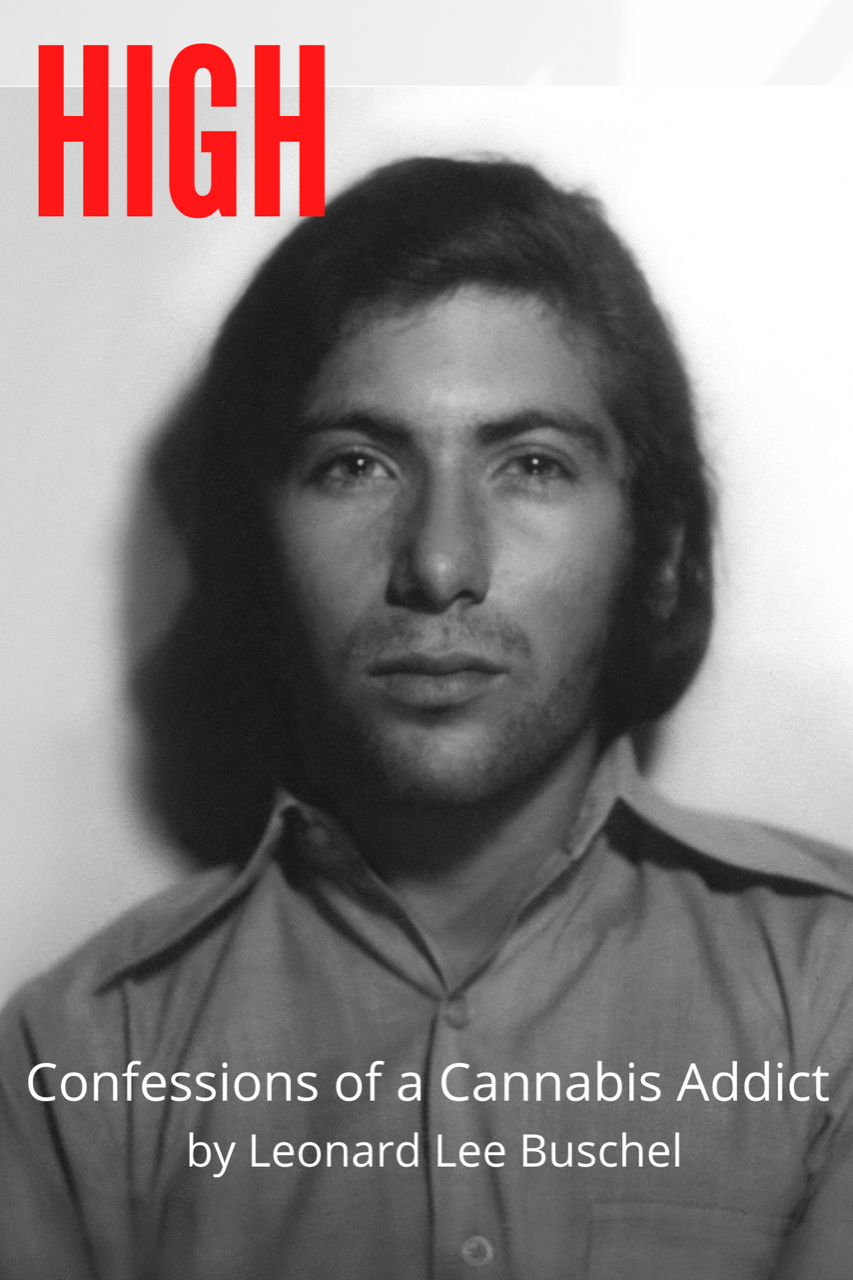

Picture This FBI Close Call

After I made it back to Philly, I secured honest employment with the Philadelphia School Board in their Audio-Visual Department as a photographer. I photographed people in various occupational settings, such as automobile mechanics, airport workers handling luggage, postal workers sorting mail, and waiters in restaurants. I photographed people in jobs that required training but not a college education. My photos were then used in a multimedia presentation to lure, or encourage, the non-liberal artsy students into vocational/technical high schools to learn a trade.

One of my favorite moments as a photographer was being on an assignment for The Drummer, Philadelphia’s version of The Village Voice. I was having lunch with movie greats John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands. When I asked Gena to pose for me, she gave me the thumbs up in the air and spitting gesture, just like she did in their film A Woman Under the Influence, starring Rowlands, Peter Falk and directed by Cassavetes.

John, seeing this, leans over to me and whispers, “You’re the only photographer she’s done that for. She must really like you.” That compliment from the greatest couple in cinematic America has continued to lift me up during moments or months of despair.

My boss at the school board, a sweet preppy college graduate cat, drove me home one day and wanted to hang out at my place. As we walked in, my roommate took me aside and whispered, “The FBI was just here. An envelope was sent to you from Bogota, Colombia. I think there was cocaine in it. The post office delivered the package, and 10 minutes later, the FBI came through the door. I knew not to open the envelope. Your name was on it! They’re coming back to question you or arrest you.”

My friend Brad of Israeli ménage à trois fame had sent me 27 grams of coke. We were both under the misunderstanding, false impression, wrong assumption that any envelope under an ounce (28 grams) never got inspected or flagged at the post office. And since my father, Morris, died during a car ride home from his night shift at the main post office, I thought I had a guardian angel looking over my mailing maleficences. In future years, I would call on his blessings many times, as a big part of my business relied on sending pot and coke through the U.S. Postal Service.

I said to my boss, “Ken, something personal has come up. I’m sorry, but I think it would be best if you split. You’re not going to want to be here. I’ll see you in the morning.” (I prayed)

He gave me a very perplexed and concerned look and left.

Because my roommate said they’re going to be back in a half hour, I knew exactly what I needed to do. Take a 5 mg Valium! Because a 10 might have been too much. I know that I’m going to have to calm down for this but not be too drowsy. Sure enough, a half hour later, I’m being interrogated by the goddamn FBI. Yes, they do all wear jackets and ties.

Drawing upon my skills at acting, improv and lying, I concocted a story about a guy I met at Dirty Frank’s, a bar I frequented frequently. “We ordered a couple Rolling Rocks and checked out the bar for chicks,” I told them. “He said he was a student at PCA [Philadelphia College of Art] and that he enrolled midterm because he and his girlfriend just moved to Center City from Pittsburgh. We talked about art and shit about Andy Warhol being from Pittsburgh . . .”

“Okay! Okay!” said the agent, who was trying to shut me up. “How the fuck did he know your address?”

They had already found some weed, so I said, “Oh, we came back here to smoke a joint, and I figured the guy wasn’t out to blow me or anything because he said he had a girlfriend. He must have written down the address. It’s right next to the front door.”

I lived in a 200-year-old trinity house, otherwise called a Father, Son, and Holy Ghost house because they have a spiral staircase connecting three floors and are unique to the very Catholic city of Philadelphia. Each floor is its own room. This particular dwelling was built to house the servants of the Founding Fathers who lived on Pine, Spruce, and Delancey Streets. Those FBI guys searched the place top to bottom.

It took them awhile, but they found some more weed. Not much, but it was the ‘70s and weed was illegal. Meanwhile, I am in state of shock; on the precipice of passing out or accepting my Oscar. Just then, I realize that one of the agents is Bart Freidman, the son of the fruit and vegetable man who ran the fruit and vegetable store where my mother and I shopped every week. My first thought: I couldn’t believe that a Jew had become an FBI agent.

I look at him; he looks at me. At that moment, he realizes he knows me. “Hey, I know this kid and his mother,” Bart says. “He’s a good kid, leave him alone. Let’s get out of here.”

They took the package of coke and the weed, and that was the end of it.

In that eternal moment of gratitude, I knew that God was on my side. If it had been a different FBI crew, the story might have ended with the bang of a gavel and the slam of a prison door. After all, they found two controlled substances—including one whose foreign origin broke several federal laws.

Serendipity has played a large role in my life. Dangerous events by chance often reversed to my benefit. Through dumb luck or divine intervention, most of the tense situations in which I found myself ended with magical moments. Was it just fate or some sixth sense I had about navigating such situations?

Looking back, if I had gotten busted that day in the hazy, late-afternoon sunshine, I wonder whether my entire life would have been completely different. If I had a rap sheet or seen the inside of a prison with Bubba as my cellmate, maybe I wouldn’t have become a drug dealer. Maybe I would have been better off if fear of going back to prison would have sent me down a more traditional path.

I also think about how life might have turned out had I stayed at the school board, made a decent living, had a job for life (unions in Philly at that time were unbreakable) and retired with a pension. I’m sure I would have still been a drug addict. I just would have had to find other ways to pay for my addictions. In AA they say, “We shall not regret the past, nor wish to shut the door on it.” Well, I do regret the past. Smoking pot every day for 26 years was not the sharpest decision I ever made.

When I quit the school board in 1973, I was making $200 a week. (That was the equivalent of $1000 back then.) My boss told me I’d never make that kind of money again.

#

Despite some adverse consequences so early in my profession, I pursued my chosen path with gusto. Being a dealer wasn’t just about dealing drugs. It was who I was. My chosen pathway seemed perfectly suited to my God-given talents. Besides, I was now also addicted to expensive nights out on the town—restaurants, concerts, and Broadway shows. And my love of sex and television? (I bought the first Sony Trinitron before anyone else I knew. See photo in Chapter 1.)

Once I was living in a cool Pine Street apartment with cathedral ceilings. I was in the loft bed one afternoon. To be more specific, I was in Patricia, a young and energetic art student who elevated craft services of sex to an artistic multicourse meal worthy of any celebrated chef.

As she and I delved into the delicious main course, the radio DJ announced that Rod Serling had died. Obviously, Patricia and I were too busy enjoying each other to pay any attention to the DJ’s obit on the radio. It was 30 minutes later when, relaxing with a postcoital joint, I said,

“Hey, did you know Rod Serling died?”

“Yeah,” she said. “Died from a heart attack.”

We cracked up laughing. Patricia and I had both believed the other was so engrossed in passion, in our conjugal visit, that the untimely death of one of television’s premier screenwriters, and host of The Twilight Zone, couldn’t penetrate our combined crescendos of ecstatic vocalizing.

The Twilight Zone was one of those must-see TV shows that I and perhaps millions of other Americans would look forward to watching once a week. The Twilight Zone was the vision of Emmy Award–winner Rod Serling, who was host and writer for more than 80 episodes of the original show’s 150-plus episode run. I remember watching an eclectic blend of horror, sci-fi, drama, and humor. It was in black and white, but in my mind, it was bursting with colorful and imaginative content—and for a kid, it could be scary as shit in its darker themes. The extraordinary 1956 TV production of Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” which is one of my all-time favorite tear-jerkers, was made into a full-length film in 1962.

The Twilight Zone brand published novelizations of 19 of Serling’s scripts, as well as several volumes of original short stories edited by Serling himself. I read them all. Serling was one of the most radical writers working in television at the time. He dealt with socially relevant, controversial, left-wing issues disguised as The Twilight Zone. He was a prophet and died way too young from smoking himself to death. At the end of his short teleplay, “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” Serling says:

“The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, and prejudices—to be found only in the minds of men. For the record, prejudices can kill. And suspicion can destroy. And a thoughtless, frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all its own—for the children and the children yet unborn. And the pity of it is . . . that these things cannot be confined . . . to the Twilight Zone.”

#

My drug dealing really took off when my mother opened a family American Express account and gave me a credit card with my name on it. Now I could rent a car to transport the pot I purchased. No one wanted to use their own cars in case they got busted. Now I could move up to the big times.

When I was introduced to The Fox, a dealer in Miami, I became what’s known as a middleman. I bought from the people who bought from the smugglers, and I sold to the people who didn’t know the people who bought from the smugglers. I preferred to buy weed in south Florida, usually 100 pounds at a time. It cost $300 a pound, and I would drive it or have it driven to Philly and sell them for $400. And make $100 per pound. If I sold them all at once, I’d only make $30 a pound, but that’s still $30 x 100, and it was enough to live on for a month.

Drug sales were not always consummated in cash. In 1975, I received a classic 1965 cream-colored, four-door Mercedes Benz sedan as partial payment for a pot sale. About one year later, I was so distracted watching a girl walk down Pine Street that I drove into the rear end of another car. I jumped out, removed my car’s license plates, scratched out the VIN number, ran six blocks to Hertz, rented a car, and made it to my appointment to pick up a pound of Thai weed on Front Street. That means I didn’t need cash. And I wasn’t actually going to Front Street; the dope was being “fronted” to me.

God blessed me with the inborn ability to make friends and influence purchasing opinions. There is nothing like taking a huge buyer, who supplied almost all of Staten Island, into a Ft. Lauderdale pot warehouse with armed Columbian security guards and convincing him he should take an extra hundred pounds on credit because his Winnebago still had some empty space left in the shower compartment.

Any negative stress associated by such scenes was easily dissipated with a vacation to St. Barts, Jamaica, or London, appreciating its museums, theaters, curry houses, brothels, and music venues, from Ronnie Scott’s to corner pubs with local troubadours. One time while on St. Lucia, waiting to take a four-day Windjammer Barefoot Cruise, a really cool skinny kid befriended me and showed me around the island before extorting most of the pot I had on me, because he threatened to turn me in the local police, and marijuana possession on St. Lucia was considered an arrestable crime. The little criminal left me with some weed so I could still enjoy the cruise.

Coming back via Puerto Rico, I was busted in the airport for having one joint on my person. It was my last joint, and I’d planned to smoke it while walking around San Juan. Because I was still in the airport, on federal property, I only got a citation. Had I been caught with it while walking around San Juan, I would have been arrested.

One of my favorite vacation spots became Negril, Jamaica. Reggae music was everywhere, as if it were coming from the jungle at all times. The oceans are clear and great for snorkeling—you can see 20 feet down. The cliffs are to “dive” for. The food is amazing. If the chicken isn’t jerked, I don’t want it, and the plantains better be hot.

As good as the pot was there, I always took my own. After the plane lands in Montego Bay, it’s a good hour and a half drive to Negril. And I had to get high on the way. Plus, the weed I took there was always better than theirs. My Hawaiian always impressed the locals. And, if you’re looking for a way to stoke your self-esteem, impressing the local Rastafarian chief with your weed is one of them.

One year on a Full Moon New Year’s Eve in Negril, after drinking plenty of vodka and snorting a bunch of Ecstasy, I decided to dive off a 20-foot-high cliff to impress my girlfriend Melissa. I wanted to fly right into the Full Moon. Earlier in the day, I was snorkeling in this very same place. While in mid-air I remembered seeing some thorny black sea urchins while snorkeling. There is no beach here, only a ladder stuck into the side of the cliff that you must climb to get out of the water. That’s where the ugly urchins had been congregating—near the ladder.

Simultaneously I saw myself getting stung by said sea urchin, having a deadly allergic reaction, drifting off, corpse-like, into the middle of the beautiful Caribbean Ocean. Then reading the headline in the Jamaica Observer: American Dies in Negril Diving Accident and no one cares. Sort of the way I felt when I thought I was having a heart attack in a bungalow at The Chateau Marmont where Jim Belushi overdosed and died. Except my obituary would not be on any front pages, it would be one of those little classifieds you have to pay for when someone of no renown dies.

#

I had adjusted well to my James Bond–type lifestyle of international intrigue and had no regrets for choosing to become a drug dealer, but I still longed to be part of anything cinema. In 1975, I went up to New York City. I was anticipating seeing my buddy Robert Downey Sr.’s film Greaser’s Palace (Bob and I had been friends for over 40 years, until his death on July 7, 2021, left a gaping hole in my heart). The film stars Allan Arbus (Diane Arbus’s husband) as Jessie, a man who heals the sick, brings the dead back to life, and tap dances on water, a resurrection story masquerading as a western.

After the screening, I went over to a very famous Brill Building songwriter’s apartment and spent the night. I had met her earlier that year at my Genius Cousin Bobb’s father’s funeral. While the guests were sitting shiva and nibbling on deli snacks in one room of the old apartment in West Philadelphia, the songwriter and I were nibbling on each other in the bedroom. She was about 10 years older than me, a little heavy, and undeniably, a heavyweight seductress. For some reason, the energy at the funeral had elicited a tremendous erotic charge from both of us. It was a crazy afternoon; we were canoodling and moaning while others were mourning over the noodle kugel.

I realized that evening that even if a woman is a little bit older, and has more padding that I’m used to, as long as she’s wearing an all-black negligee, she still looks hot. The songwriter was wonderful to me, and I enjoyed every moment we shared. Perhaps she really liked me, or maybe she was simply happy to have a young guy in her antique bed. Either way, I recall her with fondness. That’s one of my experiences related to Robert Downey’s films. There are more I must mention, completely diverse in content and context.

In October 1975, I went to New York City to see a private screening of a Bob Downey work in progress film. It was first called Off the Wall, then Moment to Moment, later, Two Tons of Turquoise to Taos Tonight, then just Jive. Eventually it went back to being called Moment to Moment. The event ended at 10:00 p.m. Because the last train to Philly doesn’t leave until midnight, I had some time to fill before heading to Penn Station. I dropped down to the downtown IRT line and got off at Fourth Street. The first place I spotted was called Gerdes Folk City. I crossed the street to get a better look, and I see there’s no admission charge. So, what the fuck, I go in. It was open mic night, and a scruffy-looking crowd filled the room. I was deciding whether to stay or go when I saw Tom Waits at the bar. That cinched it. I’m in.

There’s a bar in the front room, tables and chairs in back. A girl is singing, but I’m not listening. I’m nursing my Heineken and hoping I have the patience to make it last until 11:45, giving me time to get back to the train station. Still, there is Tom Waits involved in some seriously smoky mind chatter at the bar. I keep walking around, and when I find a seat at a table, I talk to another girl with a guitar around her neck.

Then some little curly-haired guy comes into the bar with a very attractive lady. They looked much like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Holy shit, it was Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. A small film crew is following them in, and I’m wondering what the occasion is. Allen Ginsberg is also in tow. This was the first time I’d ever seen these icons in person, and what a happy coincidence that I ended up at the same club that night. It was the beginning of Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Review tour, and the whole thing was being filmed for Renaldo and Clara. It was October 23, 1975.

At first thought, I guessed it was a publicity stunt. Ten minutes later, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and Eric Andersen arrive, and they all launch into “Happy Birthday.” It’s owner Mike Porco’s 60th birthday, and some of the artists he had hired to perform in his club (when no one else would) showed up to celebrate.

Then Ginsberg begins by getting everyone in the club to chant for five minutes, which seemed like an eternity. For the next three hours, not one person left that club. We all just smiled at each other in joyous disbelief that we could all be this lucky. Dylan was doing solos and singing duets with Joan. Roger McGuinn, who was eventually inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame for his lead work with The Byrds, was also there. And I haven’t forgotten Bob Gibson. He was a key part of the folk music revival in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Joan Baez gets up and jokingly says, “I’ve known these guys for a long time, and I love them dearly. But everybody is slightly unstable.”

Around 3:30 a.m., Patti Smith blows everyone away with the loudest, most modern set of the night and a vision of what the punk rock scene would soon become. Seeing her perform was the most memorable experience of the night. Young and vivacious, she was an incredible punk rocker who was ahead of the movement, and in my estimation, was the best female performer of them all.

Finally, at 4:30 in the morning, Phil Ochs sings his heart out in that unbelievably sad voice. He hanged himself several months later in an alcoholic daze. The last known film footage of Phil Ochs was taken that night. What an honor to have been there, in the presence of a musical artist who wrote hundreds of songs in the 1960s and 1970s and who released eight albums.

Ochs is most famous for his antiwar song, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore.” He did march through life, however, with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, before committing suicide. And now, like he already said, he’s not marching anymore.

The performers weren’t singing like in a review. No, it was more like an ensemble. Each was just doing their own thing, which was more than enough for an audience who could not have appreciated it more. These singers are like miracle workers, and they have remained so for many years.

The birthday boy’s grandson (blogging in 2011) recalled the night in this way: “A cake was presented to my grandfather and ‘Happy Birthday’ was sung by all of his friends and admirers. What mattered most to him was that all had a chance to get together again.” The night ended in the wee hours with Buzzy Linhart and Bette Midler performing their hit, “Friends.” I can’t help but say it again—that was an incredibly memorable night.

At about 5:00 a.m. I walk out of the bar into the Manhattan morning mist. Too exhilarated to sit in a taxi, I start walking up Sixth Avenue. Around 22nd Street, for two long blocks, there was nothing but fresh-cut flowers. This is the wholesale florist market for the entire New York area. Trucks from all over are there to load up on the fresh flowers they’ll need that day. Flowers in Manhattan by the thousands. What a sight and smell! I’d never been up and out on Sixth Avenue at 6:00 a.m. By 8:00 a.m., all the storefronts roll down their steel doors and wait for the next morning to reveal themselves again. I walked the 30 blocks to Penn Station and dreamt about that night for the 90-minute ride home to Philly.

#

While the night following the screening of Bob Downey’s film Moment to Moment was pleasurable, my experience appearing in the film was a disappointment. I was disappointed with myself. You see, Bob and I had become good friends. He was shooting in New York, and I was going up there regularly. He just outright asked me,

“Do you want to be in my movie?”

I said, “Of course.”

It was more than an honor to be invited to be part of the film. But I had the experience of feeling honored by Bob before. That crossing of our paths started when I saw a notice in The Distant Drummer, our local underground newspaper, that underground filmmaker Robert Downey Sr. was showing a work in progress at Temple University. My brother was with me, and I said, “Let’s go see the man who made Putney Swope.” It was one of our favorite films. “He’s showing his new movie at Temple tonight.”

“You go and bring him back to my place,” Brother Bruce said jokingly.

I attended the screening. Afterward, I went up to Mr. Downey and said, “I don’t know how you feel about the government of Pakistan. But how do you feel about its hashish?” Bob seemed to like that question. I offered him a ride to the train station so he could get back to New York.

“Sure,” he said. But once we were in the car, I told him I had to make a quick stop at my brother’s place to borrow a hash pipe. We got to his building and rang the doorbell. He lived on the third floor. Brother Bruce opened the window and looked down.

“What do you want?” Brother Bruce yells.

I yelled back, “I’ve got him.”

“Got who?”

“Here he is. It’s Robert Downey.” I saw Brother Bruce’s mouth mouth the words, “Holy shit.”

He buzzed us in. From the moment the door was opened, an all-night rap session took place. There we were, in the presence of someone we respected and admired. Putney Swope was our first exposure to an absurdist work of genius. A comedy that imagined a better world, especially for African Americans. Years later, when Downey first met Richard Pryor, Pryor exclaimed, “You mean you ain’t black?”

We spent the next couple hours talking about life and film, the afterlife, religion, sports, gambling, you name it. It was like consulting a human opinionated Wikipedia with questions about every important aspect of life. Eventually, we realized that it was too late to catch the last train for New York. So we brewed a pot of coffee, hot water for tea (for Bob), and kept the conversation going all night. Cocaine wasn’t on the scene yet, otherwise I’m sure I would have had some with me. When I did eventually start snorting coke, I had a vial in my pocket for 13 years. Never a day without a full vial. You can do that when you’re a coke dealer.

A couple months later, I sent Bob a letter asking him if he ever needed any crew members for his next film, I would work for free. I would rather sweep the floor on the set of a Bob Downey film than make a fortune selling stocks for a brokerage company. (Not that that was ever an option.) That’s my motto for living. “It’s not what you do, it’s who you do it for.” The letter (real ink, paper, and a first-class stamp) did eventually open the door to a film role for me.

I remember the day we filmed in a downtown loft, because the night before, I was with a girlfriend who was into Arica, a human potential movement started in 1968 by Bolivian-born philosopher Óscar Ichazo. It was based on Sufism, transpersonal psychology and the teachings of Stanislav Grof. She and the other Aricans living in New York all had penthouse apartments because they believed that being as close to the sky as possible was akin to being on a mountaintop. So, they all had the highest apartments they could find in the tallest buildings they could afford. They hired carpenters to build platform beds right at window height. When you looked out at night, you were looking out and down, at all of down-and-out Manhattan. Maybe it’s not down-and-out for everyone, just the tens of thousands living on the streets and hundreds of thousands doing hard work for minimum wage. The view was magnificent. She and I stayed up until morning getting higher than her platform bed. She was a little older, and very well versed in keeping a young man up all night, so to speak.

When I showed up on the set the next morning, I had a horrific hangover. I regret not showing up healthier because I didn’t do my best acting job. My uncontrolled drug use the night before ruined my scenes, most of which ended up on the cutting room floor. Bob deserved better than what I gave him. I had performed in Philadelphia at local playhouses, and in high school plays, but my performance in Bob’s film sorely suffered . . . as did I. I didn’t intend to do coke and sex all night, but once we got started, there was no turning back on our backs.